5 Evidence-based Tips for Ordering Blood Cultures

- Benjamin Heymans

- Feb 1

- 5 min read

Updated: 4 days ago

In medicine, many practices are passed down through generation of doctors without rigorous evidence. In this way, I learned when to order blood cultures, based on traditional rules, such as drawing them when CRP is elevated or when a new fever develops. However, these practices often lag behind the current evidence. Below are five evidence-based recommendations to enhance the diagnostic yield and clinical utility of blood cultures.

Tip 1: Maintain a low threshold for ordering blood cultures.

The diagnostic yield of blood cultures is generally low, ranging from 4-13% across different studies (1-3). While some studies suggest methods to increase this yield (2,5), these approaches may unnecessary restrict the use of blood cultures. Blood cultures should remain part of the workup for clinically deteriorating patients for two key reasons:

a) Clinicians often struggle to accurately recognize sepsis. In one study, intensive care specialists were asked to classify five case vignettes as sepsis or septic shock. Responses varied widely, highlighting the subjective nature of sepsis diagnosis (4).

b) Blood cultures play a major role in antibiotic stewardships. Positive cultures can guide de-escalation of antibiotics based on susceptibility data, whereas negative cultures, whether or not in combination with an alternative diagnosis, can support earlier discontinuation of antibiotics.

Tip 2: Order at least two sets (and preferably three) with every bottle adequately filled.

Tip 3: Do not wait for fever to collect blood cultures.

Traditionally, blood cultures are drawn at the time of fever, based on the hypothesis that the diagnostic yield is higher during these periods. Supposedly, bacteria are only intermittently present in the blood, releasing cytokines and resulting in fever (6). However, several studies have debunked this hypothesis, most notably Riedel et al (7), which found no correlation between body temperature and the likelihood of positive cultures. Additionally, the timing interval between blood cultures does not affect their diagnostic yield (6).

Modern microbiological techniques can detect very low bacterial concentrations, (1) with the main limitation being the volume of blood drawn. Therefore, the decision of ordering blood cultures should not depend on the presence of fever.

A quite old study observed that increasing the blood volume from 20 to 40 ml increased the detection of bacteremia by 19%, with an additional 10% rise when volume was raised from 40 to 60 ml (8). Currently guidelines recommend drawing at least two sets (so four bottles in total) when blood cultures are indicated (1). Importantly, each bottle should be filled with 8-10 ml of blood for optimal detection. However, real-world data from Spain showed that, on average, only 5 ml of blood was collected per bottle (9).

In general, drawing a solitary blood culture set should be avoided due to the lack of sensitivity (too little blood volume drawn) and the difficulty in distinguishing contamination from true positives. One possible exception is checking for clearance of bacteremia: in one study, a single culture taken four days after onset of antibiotic therapy had a sensitivity of over 95% for excluding ongoing S. aureus bacteremia (10).

Tip 4: Multiple sets can be taken from one draw.

A common practice is drawing every set of blood cultures from a different site (multi-sampling strategy). Old data, after all, indicated that multiple draws were more sensitive, although this was likely due to the small volume of blood inoculated (1). Furthermore, multi-sampling strategy might help to distinguish pathogens from contaminants.

However, some recent evidence supports a single-sampling strategy, with one prospective study showing its superiority over a multi-sampling strategy (11). Moreover, there are some additional arguments to implement (at least partly) a single-sampling strategy.

1. As mentioned before, the total blood volume drawn is the main determinant of detecting a bacteria, a finding supported by numerous studies.

2. Some patients are difficult to bleed; a multi-sampling strategy in these cases might lead to discomfort, waste of time and increase in number of solitary blood cultures.

3. Single-sampling strategy reduces the risk of forgetting the second set (1).

Nevertheless, single-sampling strategy requires a different way of diagnostic reasoning. For instance, contamination in this case should be defined by the number of positive blood cultures and the type of microorganism (1). Moreover, some diagnostic criteria, such as the modified Duke criteria for endocarditis, require the identification of the same micro-organism from two separate draws (12).

Tip 5: Not every fever requires blood cultures.

A common teaching is that every feverish patient requires blood cultures. This practice is widespread, especially during night shifts (13). An American prospective study, for instance, showed that blood cultures were commonly considered an essential part of the diagnostic workup for fever (13), although the current literature agrees that fever alone is a poor predictor for bacteremia in hospitalized patients (1,3,7).

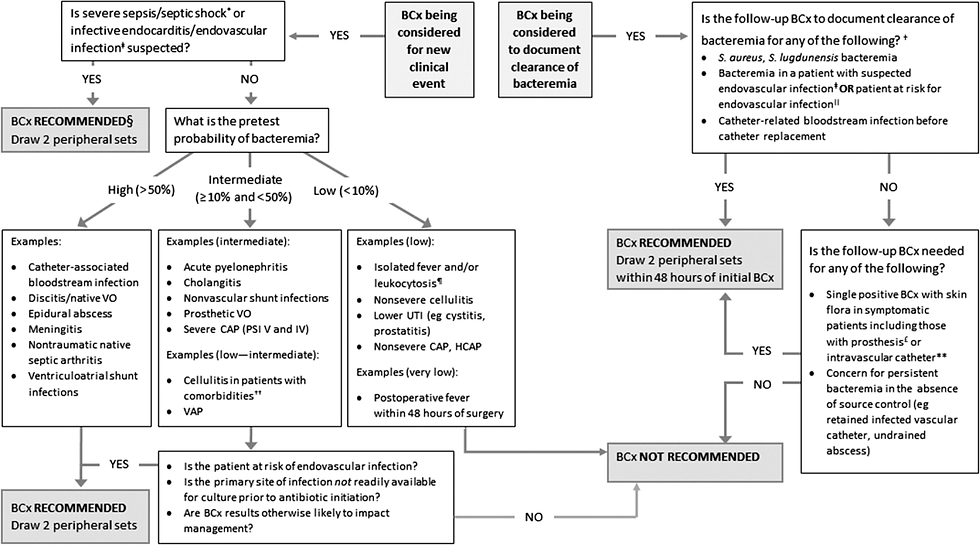

Moreover, not every infection requires blood cultures. The latest Dutch guideline on community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), for example, advises against drawing blood cultures in CAP due to their low added diagnostic yield (14). The same reasoning most likely applies to other infections such as appendicitis, cholecystitis or prostatitis. Furthermore, algorithms can help streamline blood culture ordering. One study using such an algorithm observed a 30% reduction in the total number of blood cultures taken on the ward (2). An example of such algorithm is shown below (15).

References:

1. Lamy B, Dargère S, Arendrup MC, et al. How to Optimize the Use of Blood Cultures for the Diagnosis of Bloodstream Infections? A State-of-the Art. Front Microbiol. 2016 May 12;7:697.

2. Fabre V, Klein E, Salinas AB,et al. A Diagnostic Stewardship Intervention To Improve Blood Culture Use among Adult Nonneutropenic Inpatients: the DISTRIBUTE Study. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 Sep 22;58(10):e01053-20.

3. Foong KS, Munigala S, Kern-Allely S, et al. Blood culture utilization practices among febrile and/or hypothermic inpatients. BMC Infect Dis. 2022 Oct 10;22(1):779.

4. Rhee C, Kadri SS, Danner RL, et al. Diagnosing sepsis is subjective and highly variable: a survey of intensivists using case vignettes. Crit Care. 2016 Apr 6;20:89.

5. Ryder JH, Van Schooneveld TC, Diekema DJ, et al. Every Crisis Is an Opportunity: Advancing Blood Culture Stewardship During a Blood Culture Bottle Shortage. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024 Aug 23;11(9):ofae479.

6. Fabre V, Jones GF, Hsu YJ, et al. To wait or not to wait: Optimal time interval between the first and second blood-culture sets to maximize blood-culture yield. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2022 Mar 25;2(1):e51.

7. Riedel S, Bourbeau P, Swartz B, et al. Timing of specimen collection for blood cultures from febrile patients with bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2008 Apr;46(4):1381-5.

8. Li J, Plorde JJ, Carlson LG. Effects of volume and periodicity on blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1994 Nov;32(11):2829-31. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2829-2831.1994.

9. Bouza E, Sousa D, Rodríguez-Créixems M, et al. Is the volume of blood cultured still a significant factor in the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? J Clin Microbiol. 2007 Sep;45(9):2765-9.

10. Stewart JD, Graham M, Kotsanas D, et al. Intermittent Negative Blood Cultures in Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia; a Retrospective Study of 1071 Episodes. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 Nov 18;6(12):ofz494.

11. Dargère S, Parienti JJ, Roupie E, et al. Unique blood culture for diagnosis of bloodstream infections in emergency departments: a prospective multicentre study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 Nov;20(11):O920-7.

12. Fowler VG, Durack DT, Selton-Suty C, et al. The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases Criteria for Infective Endocarditis: Updating the Modified Duke Criteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2023 Aug 22;77(4):518-526.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Schwab KE, Chang S, et al. Internal medicine residents' evaluation of fevers overnight. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019 Jun 26;6(2):157-163.

14. van Daalen FV, Boersma WG, van de Garde EMW, et al. Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults: the 2024 Practice Guideline from The Dutch Working Party on Antibiotic Policy (SWAB) and Dutch Association of Chest Physicians (NVALT). www.swab.nl

15. Siev A, Levy E, Chen JT, et al. Assessing a standardized decision-making algorithm for blood culture collection in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2023 Jun;75:154255.

Comments